I wrote the following essay over a year ago in April 2019. It was in response to a restaurant called Lucky Lee’s that opened, and swiftly closed, in New York City. At the time, I was consumed with outrage. I forwarded the story to all my non-White friends and family. Racism was not something I regularly spoke about in my day-to-day life. But it was always just under the surface, and any time something like this happened, it awakened a ferocity in me.

For a few days, I had heated conversations with confidants. Almost everyone agreed that the woman who started the restaurant was ignorant, but to my shock, not everyone saw it as a problem of racism. Like racism against Asian-Americans often is, this moment was mostly waved off, even by Asian-Americans themselves. One particularly frustrating comment an Asian-American friend made was, “I don’t see a serious problem here. Sure, her marketing language is questionable, but it’s not like only Italian people are allowed to cook Italian food.”

Over and over again throughout my life, I’ve tried to talk to people about my experience of racism. The conversations never went very far. I would frequently be met with responses suggesting I was overreacting, being sensitive, or seeing something that wasn’t there:

“It’s not like you fear for your life when you walk past a police officer.”

“Nobody discriminates against you when you walk into a store.”

“California and New York have tons of Asian people.”

I would question my outrage. I would erupt at the moment and then return to a dormant state. It’s not that it stopped bothering me. It just felt too big to do anything about, especially if other Asian-Americans in my own life didn’t seem that troubled by it. I felt too tired and too afraid to put it out there.

Even now, I hesitate to share my thoughts. Because it’s true, I don’t fear for my life when I walk past a police officer. My experiences with racism have been very different to what Black people go through. And in speaking up, I don’t want it to seem like I am at all saying it is the same. But I do believe that my experiences and perspective speak to the same system. As I think about what I can do to stand against racism, I know it has to start from speaking my truth.

There was something particularly and personally gutting when I first saw that one of the officers complicit in George Floyd’s murder is Asian. HOW? How could a Person of Color stand by and watch that be done to another Person of Color?

Of course, I can only speculate about what was going through his mind and what kind of values he, as an individual, has. But I believe it has to do with the quiet anti-Asian racism that persists and prevails through the Western world and the so-called “model minority” role that Asian-Americans as a whole have decided to identify with. I believe it has to do with deep-seated, repressed pain that is often not heard or taken seriously. And I believe that racism in any form, whether quiet and subtle or resulting in the tragic loss of life, is borne of the same system and must be eradicated in full.

As well, racism against Asian-Americans may not stay very quiet for long. With the Coronavirus having started in China, with our President calling it “Kung Flu,” and with the fractured state of our country, there has already been a rise in hate crimes against Asian-Americans. Microaggressions are evolving into violence.

So, here goes: my original essay from 2019 that is perhaps even more urgently relevant right now.

I’m sitting in a cafe in SoHo, NYC. As I look around, I am aware that I am of the minority. At this moment right now, almost every other customer is White. Notably, the entire staff behind the counter is non-White.

New York City is known as being one of the most diverse places in the world. And yet. I am always aware that I do not look like the majority of the people I cross paths with on a day-to-day basis. The majority is undoubtedly White.

The only other Asian people here in this restaurant are an Asian mother and her young child at the table next to me. When she first sat down, she asked me, in English, if I could keep an eye on the kid while she went to the bathroom. I said, “Of course,” reflecting our innate trust in each other because to each other, we are not Other.

She came back and started talking to her son in Korean, further cementing my feeling of connection with both of them.

I have been livid since hearing about Lucky Lee’s. While reading the New York Times article about the misguided, tone-deaf nutritionist / “influencer” who has shamelessly and ignorantly appropriated from Chinese culture and cuisine, my blood started to boil. I felt hot with anger, my pulse quickened, and my eyes stung with tears as I felt slammed back to my own experiences of insult as an Asian-American.

Every now and then, something like this comes up where I feel outraged and enraged. I talk to my fellow Asian-American friends: “Can you believe this? So racist! So ignorant!” I post something to that effect on social media. But my involvement has always fizzled out at that point. I, as do many other Asian-Americans, think to myself: “That person was just an idiot. We know better. We take the higher road. We’ll just keep focusing on doing well in school, getting good jobs, and buying nice homes. We’ll show them.”

I fall back in line with the role of the Model Minority. I squash my real feelings about it all — feelings that I have carried my entire life.

Because it feels overwhelming. How can I possibly effect any change on this quiet racism that has persisted against Asians in America? The fact that this woman was able to open a restaurant in New York City — not some obscure town in the middle of nowhere — using elements of Chinese culture as Instagram-ready decor while simultaneously ridiculing Chinese cuisine is more than just offensive. It is alarming. It says: Chinese and Asian culture and people are so insignificant that even though we live in this city together, we don’t really see you. It hasn’t even crossed our minds to consider your perspective.

Growing up, I desperately wished I could be White. I hated my yellow/brown skin, my extremely black hair that was so black that it was sometimes described as blue-black, my slanted eyes, and my flat nose. Looking at class pictures year after year, I felt jolted by how much I stood out along with the one or two other non-White kids. I longed for lighter skin, freckles, wavy hair, and a slimmer jawline. The more slender face shape that too many Koreans these days trade in for their “moon faces” by way of plastic surgery. I practiced smiling in a way that wouldn’t make my eyes crinkle up and virtually disappear. In fact, I still do this.

My mom packed my lunch for me in a cutesy Sanrio Little Twin Star lunchbox. She packed me Korean food that she had made with love that she knew I loved: rice, seaweed, and grilled fish or sometimes ddukbokki. She packed me chopsticks.

I remember being made fun of: “Eeew, that looks gross and smells weird. And why are you eating with sticks?”

I begged my mom to please stop packing me such embarrassing meals. No more fobby lunch boxes. “Please, can you just pack me bologna sandwiches on white bread zipped in a plastic bag and put it inside a brown lunch bag?”

I remember saying in class that sushi tuna rolls were my favorite food and someone saying, “Eeeew! You eat SUSHI? That’s raw fish! That’s disgusting!” I retorted, “It is not raw fish!” But when I went home and asked my parents, they answered, “Well of course sushi is raw fish.”

I spoke as little Korean as possible and insisted on only using forks.

I cringed as I heard my parents, who I knew were very intelligent, make grammatical errors when they spoke English and I hated the way they were responded to because of that, as if they were a bit stupid.

I wanted a golden retriever not just because I love dogs, but because, what more American dog was there?

I bit my tongue when kids would pull their eyes into slits, laugh, and say, “Ching chong ching chong!”

I pretended not to be bothered when I was called Chuey, after the token Asian character Carmelita Chu in a 90s movie called Ladybugs, because, you know, all Asians look the same.

I felt ashamed.

I hated being Asian.

My high school was not very diverse. It was a private, Catholic, college-prep school. I knew that I was lucky to be able to go to this kind of school. My parents worked hard to be able to move us to a good area and to be able to pay for private school. It should have made me feel proud and confident. But almost everyone around me was White. One year, Asians made up a mere 4% of the student body.

Because there were so few of us, we all came to know each other. I felt part of a community. Even older Asian students befriended the younger ones. I remember exchanging notes with “Asian Pride!” doodled on them.

For college, I went to UCLA. I learned that it was dubbed the University of Caucasians Lost in Asia. I relished in this reinterpreted acronym. Yes! For once, White people, YOU feel what it’s like to be the minority! I remember claims of reverse discrimination due to Affirmative Action. I remember thinking, You’re just mad that we’re smarter and we work harder! I was still reacting from feeling Less Than for most of my life. I joined KSA — the Korean Students Association. I graduated with an Economics degree and minors in English and Korean.

I finally started feeling proud to be Asian.

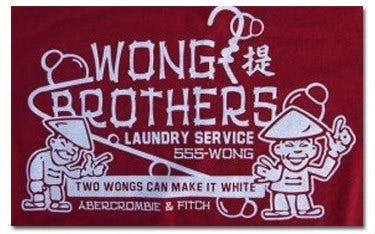

While I was still in college, in 2002, Abercrombie and Fitch produced T-shirts featuring Asian caricatures with exaggerated stereotypically Asian features — slits for eyes and Buddha bellies — wearing straw rice paddy hats. In Orientalized writing, the shirts said:

“Wong Brothers Laundry Service — Two Wongs Can Make It White”

“Rick Shaw’s Hoagies and Grinders — Order by the foot. Good meat. Quick feet.”

“Pizza Dojo-You Love Long Time: Eat In Or Wok Out”

“Wok-N-Bowl — Let the Good Times Roll — Chinese Food & Bowling”

The company actually stocked these shirts on the shelves of their stores in cities with high Asian populations like San Francisco and Los Angeles, and claimed that they thought the Asian community would love them.

I wore a shirt that spoke out against Abercrombie and Fitch, that read: “Artfulbigotry and Kitsch: Ignorance Racism Excuses.”

I don’t remember having to explain to anyone in my immediate world why Abercrombie’s shirts were so offensive. The shirts were removed from shelves and a pseudo-apology (read: backtracking excuse) was given and I moved on. The company continued receiving backlash — about the lack of diversity in their advertising and even on their sales floors — but that was nothing new or surprising to me. I had long ago already internalized that I, as an Asian person, was not good enough to have the opportunity to appear in American media in any way.

Soon after graduating, I abandoned the finance industry and became a yoga teacher. Being a yogi was what I identified with most. It was freedom from having to fight for acceptance (not least within myself) as an Asian or to remind people that I was American — “born and raised!” None of that was really relevant to me anymore because I was all about yoga. And back then, yoga was not as ubiquitous as it is today. It was something I was able to latch onto and claim for myself, something that I knew more about than most people in my life. When I would tell someone I was a yoga teacher, I was often given an immediate awe of approval. I finally felt like I had found my identity.

A few years into full-time yoga teaching in LA, I started to feel oppressed by the trajectory I perceived myself to be on. I was feeling a bit hungover from having drunk the proverbial Kool-Aid. I sensed I had lost a bit of my actual self in filling the role of Yoga Teacher. I found myself speaking with a carefully edited and controlled (read: contrived) vocabulary and wearing stereotypically yoga teacher clothes 24/7. It crossed my mind that I was probably insulting Hindus by wearing mala beads as stylistic embellishment.

I spontaneously booked a one-way ticket to Hong Kong. I wanted to live generally in Asia, but I wasn’t really sure where. I ended up staying in Hong Kong and there was something deeply resonant about being in that part of the world. The air, the smell, all my fellow Asian people. Despite not being Chinese, I felt quite at home.

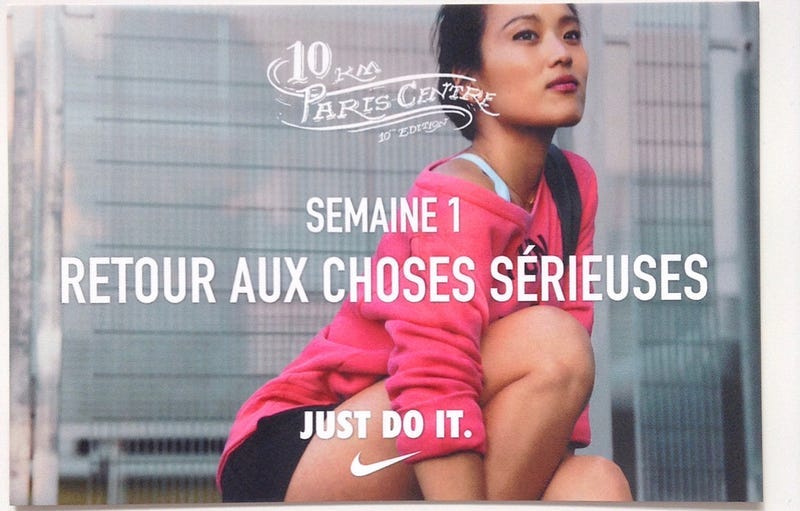

I hit a career-high while living in Hong Kong when I signed with Nike, starting a 10-year relationship as their Global Yoga Ambassador. Whatever insecurities I’d had as an Asian-American were almost instantly quelled because how could they not be? A huge American company chose me to represent yoga for them. They took pictures and videos of me and put them on billboards and apps. They sent me around the world to talk about their initiatives and how yoga was part of it all. All that outer approval temporarily silenced any inner doubts.

Much to my surprise, I met and instantly fell in love with my now husband. The reason for my surprise being that he’s White. Although I have never in my life dated or even been remotely interested in a Korean man (perhaps residual rebellion from my chopsticks-rejecting days), most of my boyfriends had been at least part Asian. But the heart wants what it wants, and I was soon living with my Englishman in London.

It didn’t take long for me to realize that there weren’t many East Asian (or the commonly used racist term: Oriental) people around. London is known for its diversity, yes, but, I couldn’t see any people that looked like me. It is only in hindsight that I understand that this bothered me. At dinners with my husband’s family and friends, nearly all of whom are White, I would lean over and whisper to him, “I’m the only yellow person here, haha!” It was as if I was attempting to preemptively poke fun at myself before anyone else could point out that I was different. Every now and then I would take it one step further and say something more outrageous to my husband, such as, “I’m the only Chinky Gook here!” I didn’t say these things in a calculated way. They just came out and I laughed while my husband was offended and probably thought I was ridiculous.

I smiled through conversations with people who “absolutely love Korean food!” by which they exclusively meant Korean BBQ, which is not representative of Korean food.

I thought, “We’ve known this for centuries!” when I saw various Asian foods becoming trendy for their health benefits: kimchi, nato, matcha, turmeric, miso, seaweed. It felt equal parts validating and violating. Validating because, well, we told you so. Violating because, well, cultural appropriation.

I inadvertently irritated my father-in-law-to-be by always calling him “Giles’ Dad” and my mum-in-law-to-be “Giles’ Mum.” Why couldn’t I just call them by their first names? I found it physically impossible to do so because it would be deeply disrespectful to do this in Korean culture. In Korean culture, it is customary to use the moniker, “so and so’s parent.”

All this deep identification with being Korean and yet, consistently throughout my life, I have heard myself say, “I’m not very Korean.” I would cite not being able to handle spicy food, not liking Korean men, not speaking the language perfectly, and not ever having lived in Korea as evidence of this claim. I envied my White-washed Asian friends whose parents exclusively spoke to them, and their golden retriever, in English.

When Giles and I were registering our intent to marry in the UK, we had to have an interview in which we would answer questions about each other to prove that we were in a true relationship and not just trying to get myself a visa. Although I was a US citizen and held a US passport, it bothered me that the government official would likely see me as an Asian, not an American

“They’re probably going to think I’m an Asian mail order bride,” I joked. My soon-to-be-husband was not amused.

At the interview, we were each asked the very straightforward question: What is your partner’s citizenship?

I (correctly) answered: British.

He (incorrectly) answered: Korean.

My eyes widened and I whipped my head around to glare at him.

He continued: Oh! I mean, SOUTH Korean.

My jaw dropped.

“American! I mean American!”

It is funny in hindsight and I get a real kick out of sharing this story. These interview type situations have the effect of making you feel like you’ve done something wrong so I know that my husband was just feeling pressure. But for me, it was a manifestation of a point I’ve been trying to make my entire life: I AM AMERICAN.

To whom, exactly, am I trying to make this point?

From a spiritual perspective, I know that the most important viewpoint is that of my own, that I must validate myself. If I am insecure about my Asian features, I need to work on self-acceptance. If I am rejecting my Korean culture, I need to look at why.

But from the larger perspective of being an Asian-American with immigrant parents, living in a racist system that has only ever made partial space for People of Color, this is not all on me to work through internally. This is on a society that celebrates and elevates one racial group over all the others, that segregates and discriminates against others based on SKIN COLOR (!!). This is on fashion brands that have incompletely represented the American people in its marketing campaigns. This is on families that did not take the time to teach their children that it’s not okay to make fun of or exclude people for looking different, sounding different, eating different. This is on Hollywood, who waited 25 years after its first-ever primarily Asian cast in the Joy Luck Club to blow everyone’s mind with Crazy Rich Asians, and who, in the interim only cast Asian actors to play token cliches.

This is on White restauranteurs that open Chinese restaurants and claim to do it cleaner and better than Chinese people. As well, it is on those who completely miss the point of our outrage over this matter.

Do you really think this is about MSG, oil, and salt?

Do you think we are dumb enough to buy your story that “Lee’s” purely came from your husband’s name? Have you never met an Asian person in your life? You really had no idea what a common Asian name Lee is? You had time to learn that bamboo, jade, and chopsticks were part of Chinese culture and use this to your marketing advantage, yet, it never crossed your mind to sense check your overall concept with a Chinese person? Did you go to China? Or at least to an actual Chinese person’s home?

It is deeply frustrating that the restauranteur’s response was one of (mock) shock. But you know what — I actually believe her. I believe her because she has blinders on. One side of the blinders reads the letters W H I T E; the other side reads P R I V I L E G E.

Until she does the work to investigate her own blindspots — simply being a White person who has not had to be aware of racism — she’s not going to understand why it was reprehensible of her to generalize Chinese cuisine as icky and causing bloat.

The thing is, this restauranteur is just the poster child of this moment of bigotry. She’s an easy target because her missteps are so obvious to everyone outside the bubble of White Privilege. She is also a social media “influencer” who is selling the “wellness” lifestyle through “clean” eating. *GAG* But the problem runs way, way deeper. The Asian-American community has been subjected to a constant hum of quiet racism since well before she or social media were born.

And no, as a group of people, we do not generally walk the streets of our cities fearing for our lives. There are benefits afforded to us as the perceived Model Minority. But racism exists in many forms and so long as it exists in any form against any group, we must all continue to speak up and to fight for equity and justice.

We are, after all, one human race.